My Top Five Ancient Texts (2025 Edition)

Given my particular areas of research (early Judaism and early Christianity) and teaching (world religions, philosophy of religion, etc.), it may not come as a surprise that much of my reading time is devoted to ancient texts, and I have gone through more than a few of them! One thing that I love about my research is how dynamic many of these ancient texts are. They can also be quite fun and exciting when you delve into them and attempt to keep in mind their social and historical contexts. I will also note here that I primarily focus on non-canonical texts here (i.e. texts that don’t appear in the Jewish, Protestant, Catholic, or Eastern Orthodox Bibles). I should also note that I am not suggesting that any of the texts below should be considered canonical; rather, I simply wish to discuss them here primarily on their literary merit.

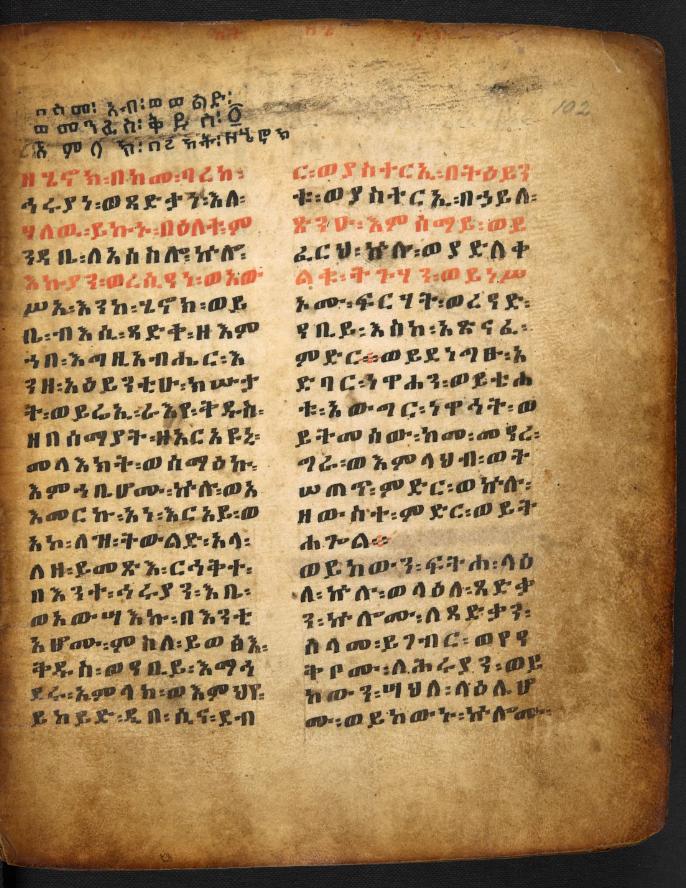

1. The Book of Enoch (1 Enoch)

My first text on the list here is a bit of special case. Though 1 Enoch (c. 3rd century BCE) does not appear in any of the biblical canons listed above, it is included in the Ethiopian Orthodox canon. I is an absolutely fascinating text. I have been absolutely enamored with 1 Enoch since my first semester of undergraduate studies. I learned about this text in the textbook for my introductory course on the Hebrew Bible at Brescia University College (Western University). Technically there are at least five sections to the collection of 1 Enoch, which likely represent five originally distinct works that were only later gathered together into a single composition.

The eponymous hero of the text here is Enoch, most well known for his depiction in Genesis 5. In Genesis 5, readers discover that Enoch never died because “God took him away” (5:21). This scant and mysterious verse has led to no end of speculation about Enoch’s fate. 1 Enoch is a later Jewish writing that attempts to address the question of what happened to Enoch after he was taken away, depicting Enoch’s vicissitudes following Genesis 5:21. Enoch is depicted as going on a heavenly journeys, where he is taken up above the Firmament (a dome that many ancient cultures believed blocked the waters of the heavens from flooding the Earth below) and he witnesses incredible topographical sites.

2. Joseph and Aseneth

This Jewish text is slightly later than 1 Enoch, typically dated between 200 BCE-200 CE. Similar to 1 Enoch, Joseph and Aseneth seeks to address a literary desideratum in the Book of Genesis. In this text, the primary question being addressed is how could Joseph, an upstanding Hebrew patriarch from the past, have licitly married an Egyptian woman, Aseneth. The short of the long here is that Aseneth goes through a very rigorous conversion account, rejecting her idols, and morning the actions of her earlier life. The son of the Pharaoh grows jealous of Aseneth’s marriage to Joseph, and later plots to kill Joseph and take Aseneth as his own wife.

What is particularly striking in this text for me is the first half of the text that focuses on Aseneth’s conversion. Aseneth is eventually called a City of Refuge, which highlights her special role within the early Jewish community. Following her confession of sins, she is met by the chief of angels and undergoes a mysterious and unconventional conversion experience, involving a mystical beehive and bees. That’s all to say that Aseneth’s conversion account is still very enigmatic to scholars, and is a tantalizing account to contemplate and attempt to understand.

3. Aḥiqar

Here I turn to a much older text, The Story of Aḥiqar, which has been preserved within many different cultural and historical settings, including 101 Arabian nights, The Fables of Aesop, just to name a couple. However, Aḥiqar is almost certainly of Aramean origin (or possibly Assyrian). This is one of the most famous examples of the lost ancient Near Eastern genre of court tales, accounts of the lives and actions of courtiers in the courts of foreign kings. There are some pretty significant additions extant in later manuscripts of Aḥiqar, so it is a little bit tricky to provide a certain and complete outline of the narrative contours of the story. In general though, the work appears to be separated into two parts, with the first part focusing on Aḥiqar’s exploits in the court of an Assyrian king, and in the second part Aḥiqar visits an Egyptian court of the Pharaoh.

I first encountered this text in my Ph.D. graduate work when I read Laurence Wills’ excellent The Jew in the Court of the Foreign King: Ancient Jewish Court Legends (Fortress, 2000). My Ph.D. dissertation similarly addresses Jewish court tales, in light of the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls. Accordingly, Aḥiqar played an important role in my dissertation as well. Particularly compelling in this text is Aḥiqar’s betrayal by his adoptive son, Nadin, who plots to have his own father murdered so that he could take up his role as chief advisor to the Assyrian king. The good news is that Nadin’s plan ultimately unravels, and Aḥiqar is eventually rehabilitated. It is this plotline that serves as one of the inspirations for Marian’s character arc in my Four Kingdoms trilogy, particularly in the first book.

4. Tales of the Persian Court

This is a case of a text that was rediscovered in the twentieth century among the Dead Sea Scrolls in 1946/7. However, it was not published in its initial form until 1956 by Jean Starcky in “Le travail d’édition des fragments manuscrits de Qumrân,” Revue Biblique 63 (1956). While the official identification number given to the text is 4Q550, that number will mean little to the average reader, so it has been renamed several times by modern scholars. I prefer the colloquial title, Tales of the Persian Court. This work is an example of a collection of Jewish court tales from the third century BCE.

Unfortunately, the text itself has several lacunae, rendering portions of the narrative rather difficult to follow. However, it appears to recount the vicissitudes of Jewish courtiers in the court of a Persian king. What I personally find interesting about this text are the different types of challenges faced by the courtiers in the account and the way that they are forced to maneuver themselves politically in the court to maintain their prestigious positions and sometimes even just to survive.

5. Setne I

Khamwas was the fourth son of the pharaoh, Ramses II (ca. 1290-1224), and was setem-priest at Memphis. He was a very famous and popular figure in Egyptian literary culture during the Ptolemaic era. This third century BCE text is a collection of court tales involving Khamwas, who serves the pharaoh in Egypt but often finds himself at odds with the rulers of Nubia (modern day Ethiopia).

While there are several different accounts about Khamwas in the king’s court, I particularly enjoy Setne I given its attention to his searching out for power in the form of the Book of Thoth. Eventually, his search leads him into a duel with another magician priest, Naneferkaptaḥ, who also recounts his earlier plights in precuring the book. Overall, this collection is a lot of fun, and it is interesting to speculate on the fact that this was once a work of popular literature in ancient Egypt.

Well that’s my list. I hope that you enjoyed it. You’ll evidently notice here my preference for court tales. I love to read about the political maneuverings of various courtiers in foreign courts to gain prestige in the face of the fact that they were essentially enslaved by their foreign overlords. I also enjoy reading the interesting astronomical speculation of 1 Enoch, as well as the mystical experiences of Enoch and Aseneth.

Have you read any of the texts above? What do you think of them? Till next time!

AK-M